Winter activity of common and soprano pipistrelles

Development of survey methods for the protection of bats during demolition and renovation of buildings in winter.

There is a widespread assumption that nursery and summer roosts are also hibernation sites for common and soprano pipistrelles. This assumption suggests that other buildings are less likely to be hibernation sites and are given little or no consideration during demolition or building insulation in winter. But is this true?

Live Cam:

At least two methods of hibernation for common and soprano pipistrelles are known: Individuals or small, dispersed groups, or large groups in mass hibernation sites. Our Central European winters are often mild, with light night frosts and occasional periods of moderate frost. When strong frosts set in, pipistrelles migrate to mass hibernacula. We do not usually know where the animals come from, but presumably from the immediate or wider surroundings. They may be common and soprano pipistrelles that change roosts because the original one is not frost-free or even too warm. Thus, pipistrelles change roosts as part of their hibernation strategy (Sendor, 2002, Simon et al. 2004).

Hibernation sites can be buildings of any size, age and type, as well as ruins, bridges and similar structures, rocks and underground sites. These are usually difficult to access, poorly visible and therefore almost impossible to control. There seem to be hardly any methods that can be used to detect or exclude hibernation sites of individual or masses of pipistrelles with a high degree of certainty at reasonable expense.

Buildings are often demolished or insulated during the winter months without considering their possible use as hibernation sites. Without this knowledge, however, there is a risk that mass hibernation roosts will be destroyed without replacement and local or even supra-regional populations of common and soprano pipistrelles will be destroyed.

It is therefore important that surveyors use the right methods to detect hibernating common and soprano pipistrelles. It would be better to carry out area-wide surveys to make these very important but also very vulnerable roosts known not only to the authorities.

In order to protect bats during demolition and insulation of buildings in winter, I am trying to sift through the existing knowledge and collect my own data in order to develop methods that will enable experts, authorities or volunteers to identify hibernation sites.

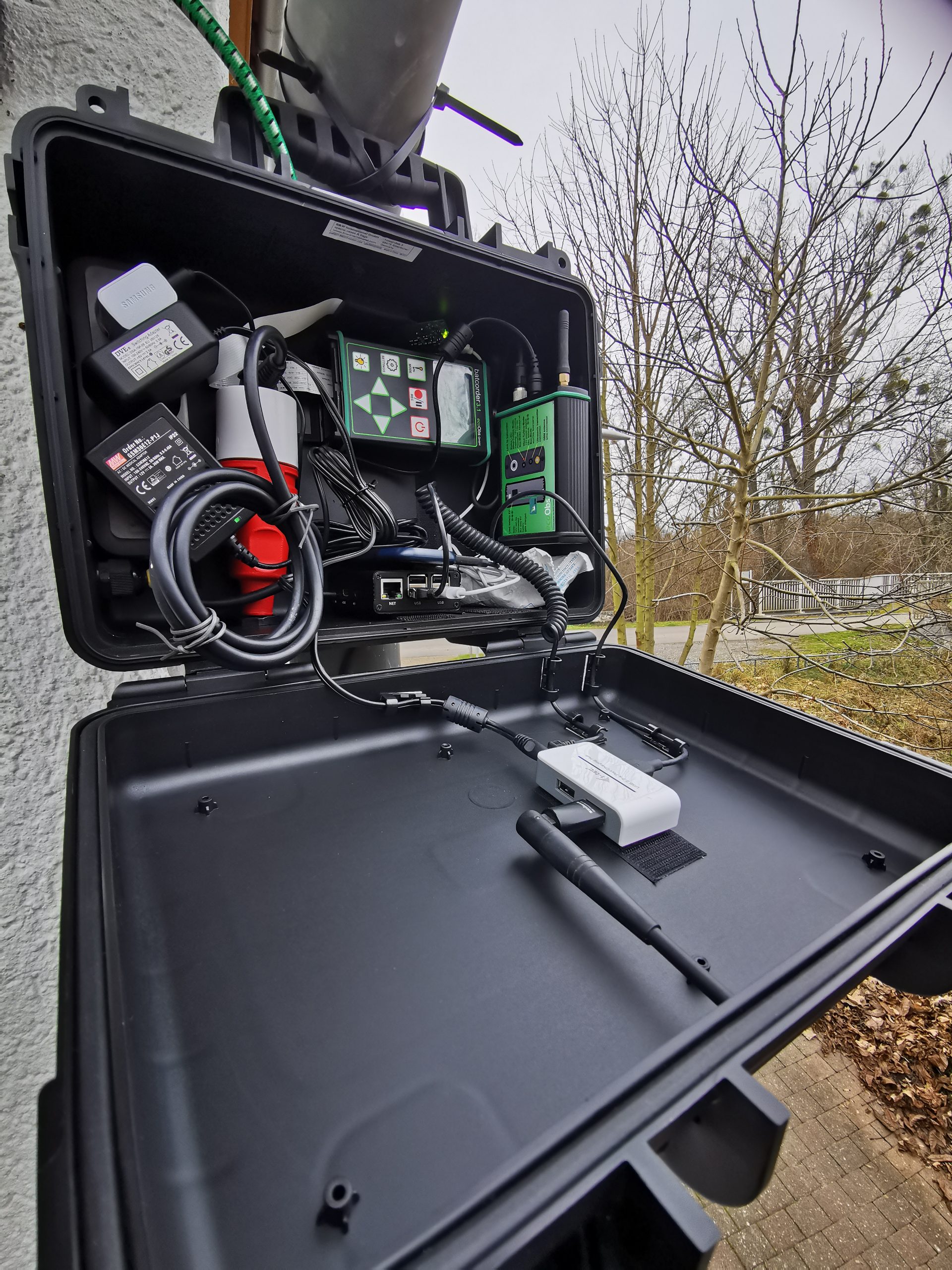

For the voluntary collection of own data, permanent acoustic monitoring was carried out at a soprano pipistrelle roost in southern Rhineland-Palatinate in the winter of 2021/2022. The roost is a single-storey former sluice keeper’s house, which provides summer roosting for 600 soprano pipistrelles on the north side of the roof. However, winter swarming activity takes place on the south side, and there is no activity at the maternity roost in winter. The acoustic data were collected with a Batcorder 3.1, for the meteorological data a weather station was installed. The data was accessed via a Raspberry Pi, which saved the daily call sequences of the night to an external hard drive and made them available for download via LTE. The final evaluation of the data with the statistics programme „R“ has not yet been completed; more detailed considerations are needed here.

Somewhat surprisingly and contrary to expectations, there is hardly any correlation of activity with temperature so far. However, there seems to be a correlation between the first frost nights in December and increased swarm activity.

At the same time, activity data were collected as part of the Master’s thesis „Winter activity of Pipistrellus pipistrellus in the city of Osnabrück (Lower Saxony) – method development and testing for better detection of building roosts“ by Jan Felix Rennack (at Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences). Likewise, in the same winter in Bavaria, the „activity of pipistrelles at hibernation sites“ was researched by Claudia Weißschädel (Fledermausschutz Augsburg), Kerstin Kellerer (Fledermausschutz Ingolstadt) and Anika Lustig (Koordinationsstelle für Fledermausschutz Bayern).

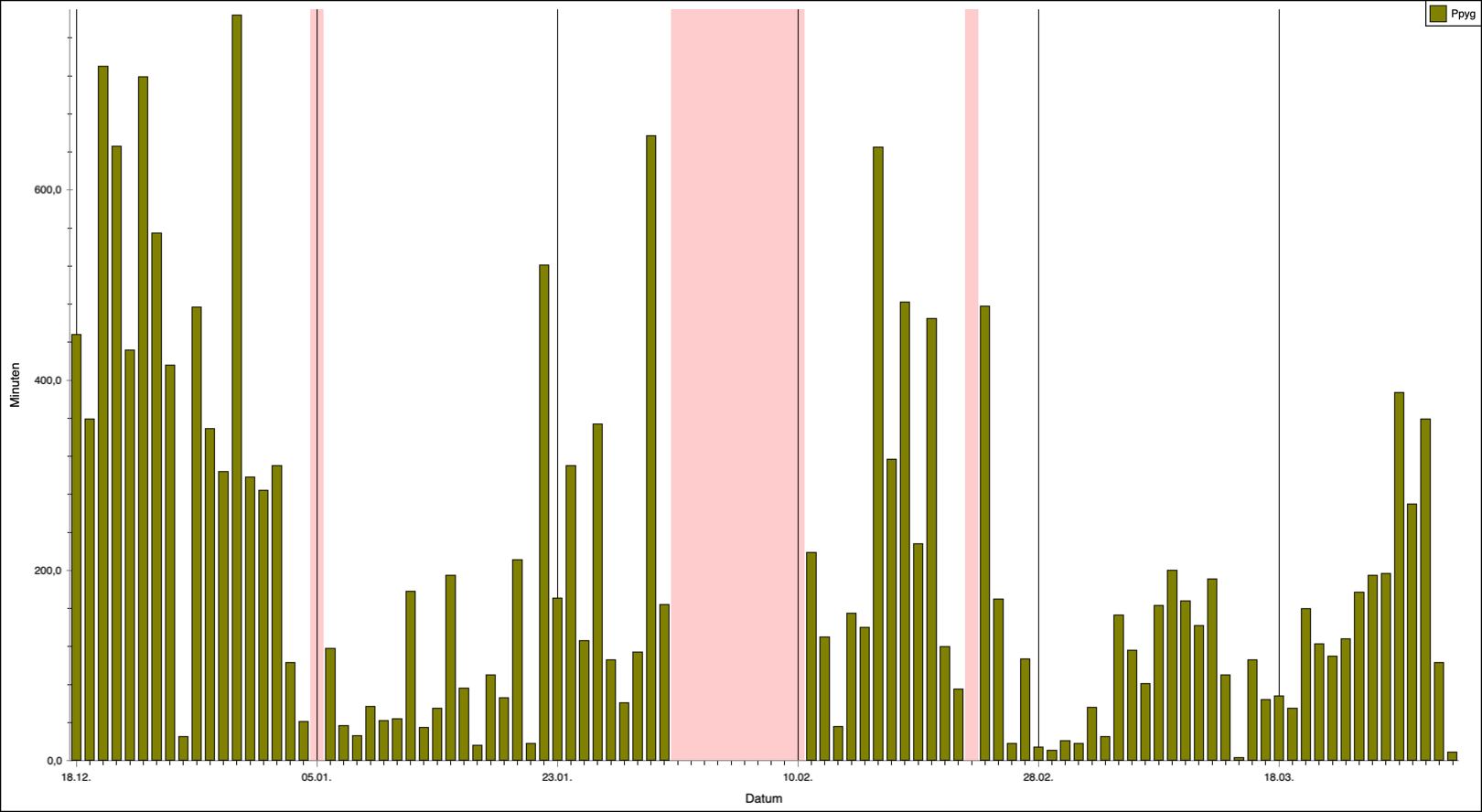

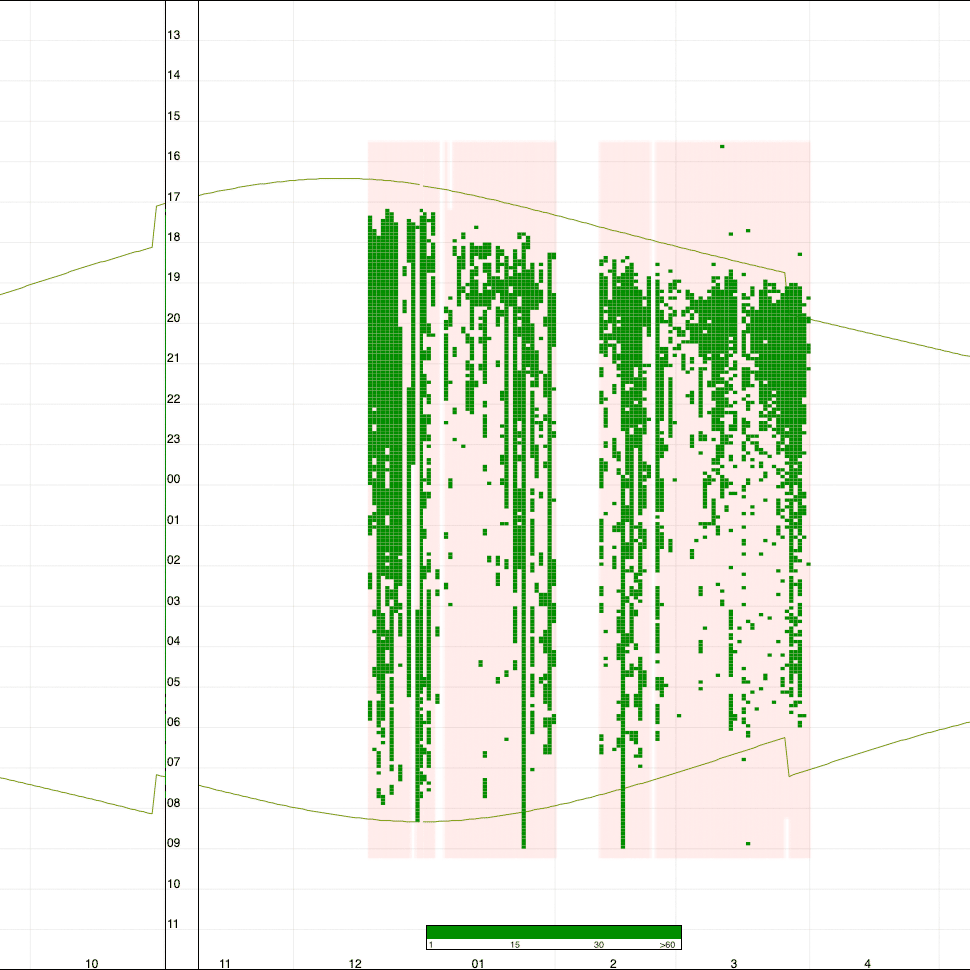

Activity in „one-minute classes“ per night from 18.12.2021 to 30.03.2022. It is shown how many minutes of activity were recorded per night. Recordings within one minute are counted as activity. Times without recordings due to technical problems are marked in red.

Activity in „one-minute classes“ per night from 18.12.2021 to 30.03.2022. It is shown how many minutes of activity were recorded per night. Recordings within one minute are counted as activity. Times without recordings due to technical problems are marked in red.

What we know so far:

August and September – Late summer midnight swarming

In the article „Swarm and switch: on the trail of the hibernating common pipistrelle“, Dutch colleagues around Erik Korsten, Eric Jansen, Herman Limpens and Martijn Boonman (2016) describe a so far little known winter swarming behavior of common pipistrelle, which occurs in individual animals but also in masses on buildings. Furthermore, the late summer swarming around midnight is described as an indication for possible hibernation sites.

Claudia Weißschädel (Fledermausschutz Augsburg), Kerstin Kellerer (Fledermausschutz Ingolstadt) and Anika Lustig (Koordinationsstelle für Fledermausschutz Bayern) describe that the roosts with late summer swarming activity host no or only very few bats during the day. In addition, animals flying out in the evening are hardly ever detected.

Timing:

Early August to mid/end September with a peak in mid to late August. Depending on the weather, the peak of swarming activity may shift well into September. In October, the activity decreases significantly.

Surveys should take place in the time window from two hours after sunset to two hours before sunrise for at least two hours.

Weather:

Precipitation-free, preferably windless and warm nights with temperatures from 15° C towards midnight.

Technique:

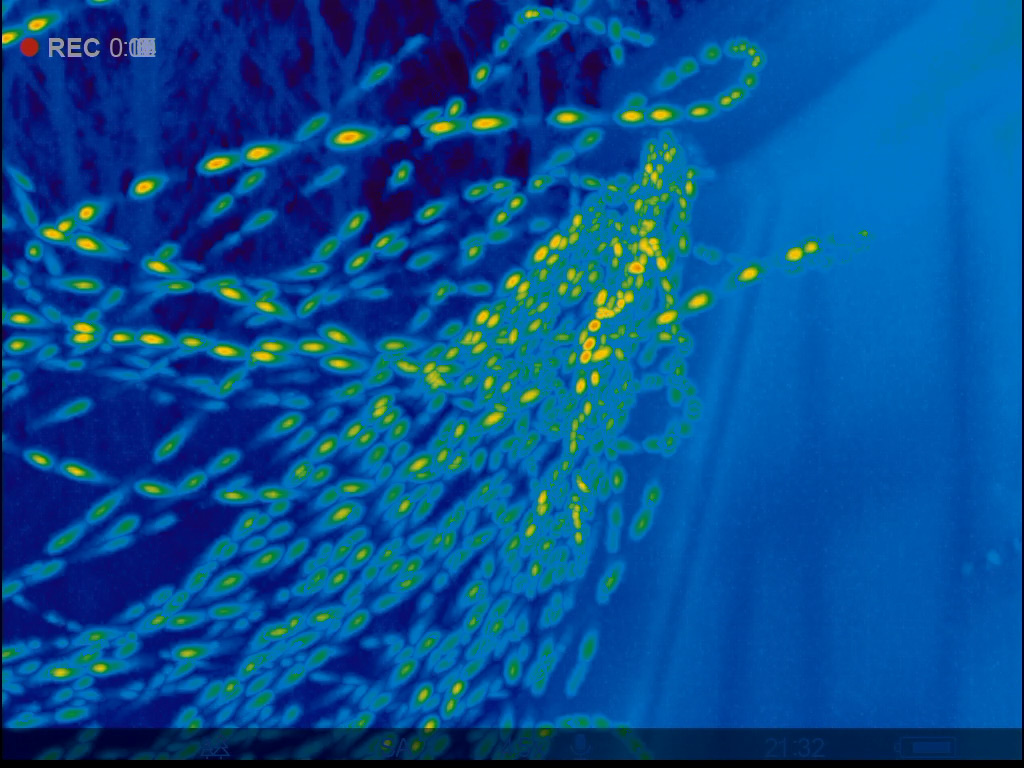

Simple detector (note the short range, nothing may be heard in high or hard to reach buildings) and preferably a thermal imaging camera. As an alternative to a thermal imaging camera, a night vision device can be used (however, with a night vision device, bats can only be detected in front of light-coloured facades and not in free airspace). A strong red-light torch or binoculars may be helpful in some cases. The survey can be carried out on foot or by bicycle, depending on the intention.

Repeat:

Repeat the survey every few (five to ten) nights when the weather is optimal.

November and December – winter swarming

In the months of November and December, there is activity almost every night on nights without precipitation – at least at mass wintering sites. The good news is that there seems to be little correlation with temperature, especially frost. This means that the search for hibernation sites is not limited to the usually few frosty nights, but can be carried out every night, provided it is not storming, raining or snowing. However, there is increased activity at least on the first frost nights, which can make finding them easier. Whether this also applies to hibernation sites with fewer individuals is currently unknown. At the very least, it can be assumed that swarming behaviour is less pronounced in smaller roosts. But be careful, because no swarming behaviour does not automatically mean that no bats are present the whole winter!

Time:

From the beginning of November until the end of December, possibly until mid-January. In January, activity dropped off significantly, at least in the winter of 2021/2022.

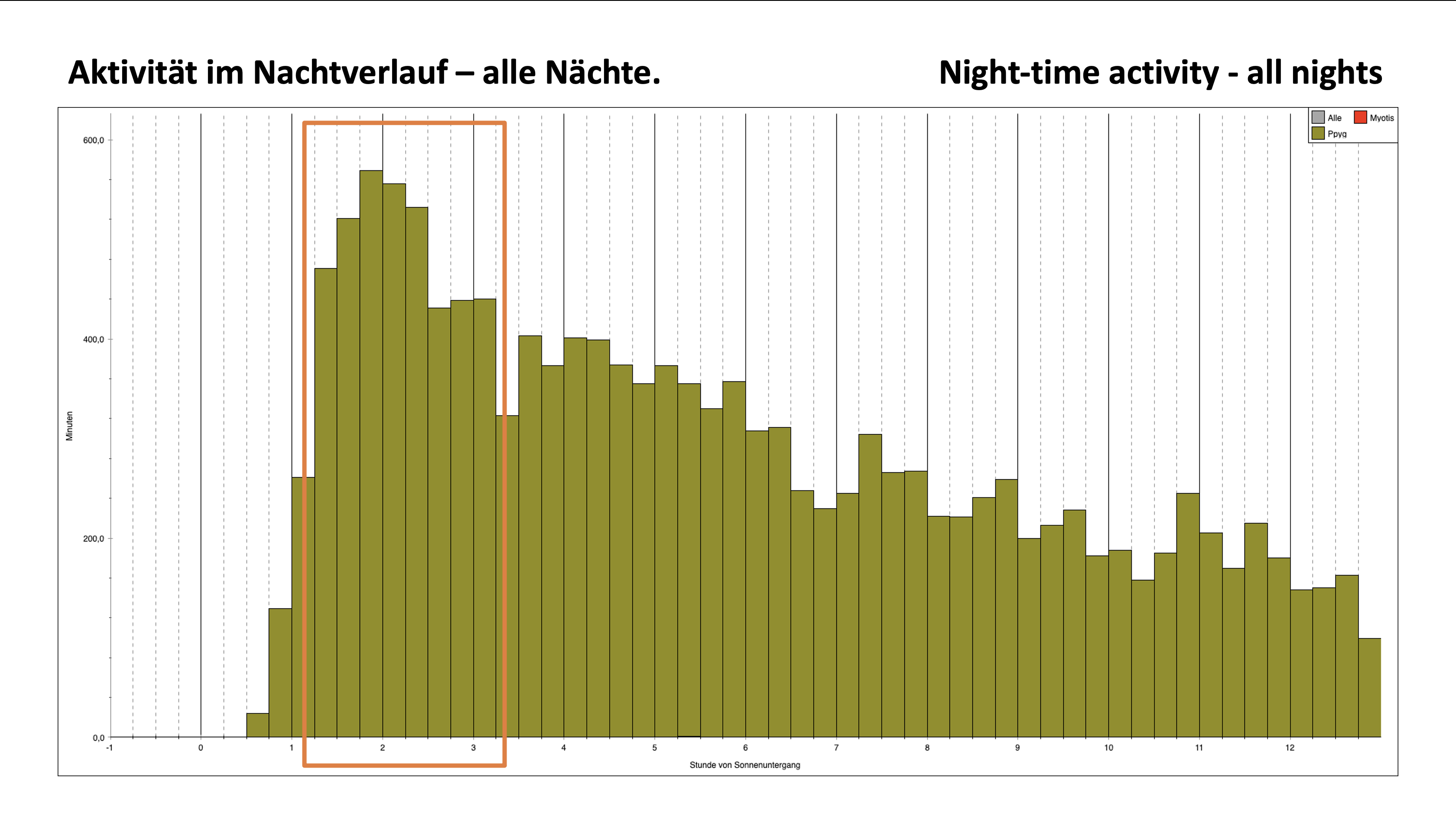

During the two months, activity could be detected every night, but with varying intensity. The beginning of swarming is at 45 minutes after sunset and shows its highest intensity between 60 and 180 minutes after sunset. On some nights there were even active bats until sunrise.

Weather:

Precipitation and storm-free nights. Temperature is hardly relevant, but possibly activity is increased during frost.

Technique:

Simple detector (note the short range, nothing may be heard in high or hard to reach buildings) and preferably a thermal imaging camera. As an alternative to a thermal imaging camera, a night vision device can be used (however, with a night vision device, bats can only be detected in front of light-coloured facades and not in free airspace). A strong red-light torch or binoculars may be helpful in some cases. The survey can be carried out on foot or by bicycle, depending on the intention.

Repeat:

Swarming can be quite small-scale, occurring only a few metres around the roost, and may be overlooked depending on the size and complexity of the building affected by demolition or renovation. Therefore, at least four appointments are recommended in the months of November and December, and significantly more for larger properties.

Activity in „one-minute classes“ during the nights from 18.12.2021 to 30.03.2022. The start of swarming is at 45 minutes after sunset and shows its highest intensity between 60 and 180 minutes after sunset. On some nights, the bats were active until sunrise.

Activity in „one-minute classes“ during the nights from 18.12.2021 to 30.03.2022. The start of swarming is at 45 minutes after sunset and shows its highest intensity between 60 and 180 minutes after sunset. On some nights, the bats were active until sunrise.

January and February

In January, swarming activity is much lower, not as steady and often does not start until 60 to 90 minutes after sunset. More visits would be needed here to avoid missing the swarming activity. January and February do not seem to be an optimal period, so caution is advised, especially here, as no swarming activity does not mean no bats are present!

From February onwards, activity seems to increase as the temperature rises.

Weather:

Precipitation and storm-free nights. Temperature is hardly relevant, but possibly activity is increased during frost.

Technique:

Simple detector (note the short range, nothing may be heard in high or hard to reach buildings) and preferably a thermal imaging camera. As an alternative to a thermal imaging camera, a night vision device can be used (however, with a night vision device, bats can only be detected in front of light-coloured facades and not in free airspace). A strong red-light torch or binoculars may be helpful in some cases. The survey can be carried out on foot or by bicycle, depending on the intention.

Visualisation of the activity between 18.12.2021 and 30.03.2022. The graph shows the activity per day in 5-minute classes, the time grid (time and months), as well as the the course of the sunset and sunrise.

Conclusion

We do not know the reason for the sometimes all-night swarming. Possibly it fulfils a social function and/or is intended to show other bats the roost. We have no information about how many of the 600 mosquito bats hibernate in the building. Do the same animals always swarm or do mosquito bats migrate to and from other roosts? The droppings left behind during swarming also suggest that the animals can feed in winter – possibly by hunting in the floodplain forests around the roost.

The data situation is currently insufficient to make more concrete statements and to identify relationships. Acoustic monitoring with on-site observations would have to be carried out from August to April in different regions at five to ten mass and also smaller roosts. Such sites would first have to be found and people would have to agree to set up and supervise the monitoring. Unfortunately, voluntary work has its limits here.

The roost in southern Rhineland-Palatinate is 400 km away from where I live. Regular monitoring would cost a lot of money and time – not to mention the equipment.

However, I would be happy to receive information about known roosts or contact bat researchers who would be willing to monitor them.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to

Henry Hermanns for technical support,

Wolfram Blug for contacts and problem solving on site,

Gabi Krivek for assistance with „R“,

Reimund Letzelter for his willingness to carry out the survey at his restaurant.

Christian Giese

for LFA Fledermausschutz NRW

Downloads:

Activity and Weatherdata: Winter 2021-20212 (3.2 MB)

A method for actively surveying mass hibernation sites of the common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) in the urban environment / Eric A. Jansen, Erik Korsten, Marcel J. Schillemans, Martijn Boonman & Herman G.J.A Limpens (Jansen et al. / Lutra 65 (1): 201-219 201)

Winteraktivität von Zwergfledermäusen (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) in der Stadt Osnabrück (Niedersachsen) : Methodenentwicklung und -erprobung zum besseren Nachweis von Gebäudequartieren (2022) von Jan Felix Rennack

(Massa-)winterverblijfplaatsen van gewone dwergvleermuizen: discussiestuk Vleermuisprotocol 2017

von Erik Korsten (Bureau Waardenburg), Herman Bouman (Arcadis) & Daniel Tuitert (Sweco)

Swarm and switch: on the trail of the hibernating common pipistrelle (2016)

Winter foraging activity of Central European Vespertilionid bats (2014)

von Andreas Zahn und Eva Kriner

Poster „Fostschwärmen“

von Christian Giese

Quelle: Bat News. No. 110 (Summer 2016). p. 8-10. Bat Conservation Trust. London.

Korsten, Erik & Jansen, Eric & Limpens, Herman & Boonman, Martijn & Schillemans, Marcel. (2016).

Swarm and switch: on the trail of the hibernating common pipistrelle.

Nyctalus (N.F.), Berlin 7 ( 1999), Heft I, S. 1 02 – 111

Die Ansprüche der Zwergfledermaus (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) an ihr Winterquartier

Von MATIHIAS SIMON, Marburg, und KARL KUGELSCHAFTER, Gießen